Thursday, April 25, 2013

Editorial decisions and challenges in upkeep will mean that Pallimed: Case Conferences will be moving to the main Pallimed website (www.pallimed.org). While we know we have not posted here with regularity for a while, the move will allow us to begin regularly posting new cases and importing the current posts and comments here back to the main site. The move will also allow the reader the chance to search on related topics on one blog and make it easier to coordinate similar materials. We will also

There may be some technical hiccups as we get the comments and posts synced up so please bear with us.

Current Email Subscribers: All current email subscribers will be imported to the main Pallimed list. I will work at removing any duplicate subscribers, plus the email updates have a very simple unsubscribe option. If you are only interested in Case Conferences we eventually will be moving to a new subscription system in the the next month which will allow for you to just choose Cases if those interest you most.

Comments: Comments will be closed on all Case Conference posts as of this posting. We will sync your comments over to the new post in addition to posting a follow-back link.

Pallimed Case Conferences (cases.pallimed.org) will stay online as an archived source, but will no longer be updated. For new cases go to http://www.pallimed.org/search/label/cases

If you are interested in submitting a Case or even potentially becoming a Section Editor for Case Conferences please email christian@pallimed.org

Thursday, April 25, 2013 by Christian Sinclair ·

Wednesday, April 27, 2011

This site will stay online as an archived source, but will no longer be updated.

Read here about the switch-over.

For the active post on this case please visit Pallimed

By Gordon J Wood, MD

Original PDF

Case:

Ms JB is a 32 year old woman with type 1 diabetes who underwent a living related donor renal transplant and a subsequent pancreas transplant. Unfortunately, both transplants were complicated by rejection and graft failure requiring re-initiation of hemodialysis in 2007. Since that time she has suffered with constant, intractable nausea with multiple episodes of vomiting throughout each day. Her symptoms were initially thought related to diabetic gastroparesis but they did not respond to metoclopramide, erythromycin or pylorus muscle botulinum toxin injections. An electrical gastric stimulator was to be placed but was aborted when a gastric emptying study was normal. Extensive workup, including laboratory studies, endoscopy, CNS imaging and abdominal imaging, was unrevealing. She received little or no benefit from adequate trials of domperidone, prochlorperazine, ondansetron, oral granisetron, promethazine, trimethobenzamide, scopolamine, mirtazapine, dronabinol, pancreatic enzymes and a proton pump inhibitor.

She underwent voluntary admission to a psychiatric hospital for treatment of any possible contributing eating disorder without any improvement. Since 2007, she has had more than 40 admissions to the hospital for nausea and vomiting. A feeding J-tube was placed to maintain adequate nutrition in 2008. She presented to the Palliative Care clinic in 2010 for further management of her nausea and vomiting. After a complete history and physical, the etiology of her symptoms remained somewhat elusive. She had nausea before her transplant and it had resolved when the kidney was working then recurred when it failed so the final conclusion was that her symptoms may be due to a poorly defined metabolic process related to her renal failure. Olanzapine was initiated on the first visit for refractory nausea and vomiting and the patient was referred to psychology and psychiatry to help with coping and to address underlying depression and anxiety. At the subsequent visit she noted some benefit so the olanzapine dose was increased and a granisetron transdermal patch was added. At the next visit her symptoms had improved dramatically with a clear temporal relation to starting the granisetron patch. She was only vomiting once or twice in the morning and was relatively asymptomatic through the day. In her first clinic visit she had vomited multiple times through the visit and appeared miserable.

At this visit she was asymptomatic, neatly dressed, wearing makeup and was thrilled at this new level of symptom control which was allowing her to re-engage her life.

Discussion: There were many factors that likely contributed to the dramatic improvement in Ms JB’s refractory nausea and vomiting. Better psychiatric care through the palliative care psychologist and psychiatrist almost certainly played a role in her overall clinical turn-around. The close attention, serial visits and supportive counseling she received in the Palliative Care clinic could also have been therapeutic. Up-titration of her olanzapine also likely was helpful. Olanzapine is an atypical antipsychotic that works on multiple receptors including dopaminergic, serotonergic, adrenergic, histaminergic and muscarinic receptors. Of particular interest is its antagonism of 5HT2 receptors which are located in the vomiting center and are not well targeted by other traditional antiemetics. Multiple small trials have demonstrated efficacy of olanzapine for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting.1 Many palliative care practitioners are now also starting to use olanzapine for refractory nausea and vomiting in patients with advanced cancer and other life-limiting conditions.2-4

Even with all of these possible contributors to her improvement, there still seemed to be a clear benefit that came with initiation of the granisetron patch. While intravenous and oral granisetron have been available for some time, transdermal granisetron (Sancuso©) is a relatively new addition to the practitioner’s toolbox for difficult to control nausea and vomiting. Transdermal granisetron was approved by the FDA for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) in September of 2008 based largely on a trial of 582 patients receiving multi-day moderately or highly emetogenic chemotherapy. Patients received either oral or transdermal granisetron and achieved equally good control of their symptoms with either method (approximately 60% in each group achieving complete symptom control). The most common side effect in both groups was constipation.5 The patch is an 8x6cm clear, plastic-backed patch and is worn for 7 days. Pharmacokinectic studies suggest that the patch delivers a dose equivalent to 2 mg of oral granisetron each day it is worn.6

It is thought to exert its antiemetic effect through antagonism of 5HT3 receptors in the gut and chemoreceptor trigger zone.7 Experience with the patch outside of CINV, however, is limited. This case suggests that transdermal granisetron may have a role in other cases of refractory nausea and vomiting. It is unclear why the transdermal form of the drug worked so much better than the oral version for Ms JB. It could reflect absorption issues, especially if she was unable to keep the pills down. It could also reflect compliance issues and may bring into question the adequacy of her prior trial of oral granisetron. Whatever the mechanism, however, the result was dramatic. Further study of this agent in settings other than CINV is clearly needed. Hopefully these results can be replicated and other patients with difficult-to-control nausea and vomiting can achieve life-changing results similar to those achieved by Ms. JB.

References:

1. Navari RM, Einhorn LH, Loehrer PJ Sr, Passik SD, Vinson J, McClean J, Chowhan N, Hanna NH; Johnson CS (2007). A phase II trial of olanzapine, dexamethasone, and palonosetron for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a Hoosier oncology group study. Supportive Care in Cancer, 15 (11), 1285-91 PMID: 17375339

2. Srivastava M, Brito-Dellan N, Davis MP, Leach M, Lagman R (2003). Olanzapine as an antiemetic in refractory nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 25 (6), 578-82 PMID: 12782438

3. Jackson WC, Tavernier L (2003). Olanzapine for intractable nausea in palliative care patients. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 6 (2), 251-5 PMID: 12854942

4. Passik SD, Lundberg J, Kirsh KL, Theobald D, Donaghy K, Holtsclaw E, Cooper M, & Dugan W (2002). A pilot exploration of the antiemetic activity of olanzapine for the relief of nausea in patients with advanced cancer and pain. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 23 (6), 526-32 PMID: 12067777

5. Boccia RV, Gordan LN, Clark G, Howell JD, Grunberg SM, on behalf of the Sancuso Study Group (2010). Efficacy and tolerability of transdermal granisetron for the control of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting associated with moderately and highly emetogenic multi-day chemotherapy: a randomized, double-blind, phase III study. Supportive Care in Cancer PMID: 20835873

6. Howell J, Smeets J, Drenth HJ, & Gill D (2009). Pharmacokinetics of a granisetron transdermal system for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Journal of Oncology Pharmacy Practice, 15 (4), 223-31 PMID: 19304880

7. Wood, G., Shega, J., Lynch, B., & Von Roenn, J. (2007). Management of Intractable Nausea and Vomiting in Patients at the End of Life: "I Was Feeling Nauseous All of the Time . . . Nothing Was Working" JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 298 (10), 1196-1207 DOI: 10.1001/jama.298.10.1196

Wednesday, April 27, 2011 by Christian Sinclair ·

Sunday, March 13, 2011

This case is now posted at Pallimed.

By Robert Arnold, MD

Sunday, March 13, 2011 by Christian Sinclair ·

Saturday, March 12, 2011

The Cases blog will be acting as a redesign test site for all of the Pallimed blogs since it has been dormant for so many months. No worries fans of great cases, it will soon be back to posting cases every other week.

Expect delays and odd formatting issues Saturday March 12th through the 14th.

Saturday, March 12, 2011 by Christian Sinclair ·

Thursday, November 25, 2010

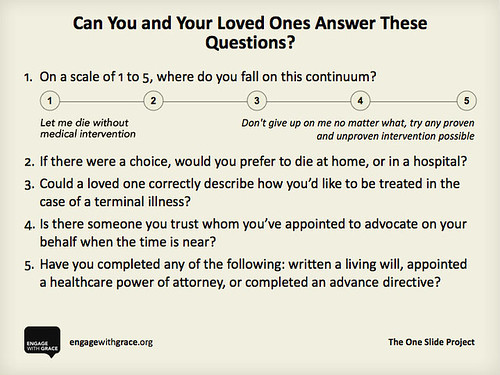

For three years running now, many of us bloggers have participated in what we’ve called a “blog rally” to promote Engage With Grace – a movement aimed at making sure all of us understand, communicate, and have honored our end-of-life wishes.

The rally is timed to coincide with a weekend when most of us are with the very people with whom we should be having these unbelievably important conversations – our closest friends and family.

At the heart of Engage With Grace are five questions designed to get the conversation about end-of-life started. We’ve included them at the end of this post. They’re not easy questions, but they are important -- and believe it or not, most people find they actually enjoy discussing their answers with loved ones. The key is having the conversation before it’s too late.

This past year has done so much to support our mission to get more and more people talking about their end-of-life wishes. We’ve heard stories with happy endings … and stories with endings that could’ve (and should’ve) been better. We’ve stared down political opposition. We’ve supported each other’s efforts. And we’ve helped make this a topic of national importance.

So in the spirit of the upcoming Thanksgiving weekend, we’d like to highlight some things for which we’re grateful.

Thank you to Atul Gawande for writing such a fiercely intelligent and compelling piece on “letting go”– it is a work of art, and a must read.

Thank you to whomever perpetuated the myth of “death panels” for putting a fine point on all the things we don’t stand for, and in the process, shining a light on the right we all have to live our lives with intent – right through to the end.

Thank you to TEDMED for letting us share our story and our vision.

And of course, thank you to everyone who has taken this topic so seriously, and to all who have done so much to spread the word, including sharing The One Slide.

We share our thanks with you, and we ask that you share this slide with your family, friends, and followers. Know the answers for yourself, know the answers for your loved ones, and appoint an advocate who can make sure those wishes get honored – it’s something we think you’ll be thankful for when it matters most.

Here’s to a holiday filled with joy – and as we engage in conversation with the ones we love, we engage with grace.

To learn more please go to www.engagewithgrace.org. This post was written by Alexandra Drane and the Engage With Grace team.

Thursday, November 25, 2010 by Christian Sinclair ·

Thursday, June 17, 2010

By Julie Childers, MD

Originally posted at the Institute to Enhance Palliative Care, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

Case: Mrs. L was a 95 year old woman who was admitted to the acute care hospital from her nursing home with decreased mental status. She was found to have pneumonia, and though her infection improved with antibiotics, her mental status did not recover and she continued to be only slightly responsive to her family, unable to eat or interact On the sixth day of Mrs. L’s hospitalization, palliative medicine was consulted to help the family with decision-making. By the time the palliative care consultant saw the patient, a temporary feeding tube had been placed, and the family had reached consensus on a trial of artificial feeding to give her a chance to regain strength, though they acknowledged that her prognosis was poor.

The next day, the patient was still unable to communicate, but was moaning and grimacing. She repeatedly tried to cough weakly to clear the copious secretions in her upper airway. The palliative care consultant recommended low doses of intravenous morphine to treat pain and shortness of breath, with a medication to clear secretions. However, Mrs. L’s attending physician was concerned that treating pain with opioids would cause respiratory depression and lead to Mrs. L’s death. The next night, the bedside nurse charted several times that Mrs. L was screaming, but they were only able to give her Tylenol for pain; she required wrist restraints to prevent her from pulling out her feeding tube. The palliative care physician was haunted by the image of the dying 95 year old woman, tied down and denied treatment for her suffering.

Discussion: Moral distress occurs when the clinician knows the appropriate action to take, but is unable to carry it out, and feels forced to give care contrary to her values. It is more often described in the nursing literature, but is beginning to come to the awareness of physicians as well. Moral distress often occurs in end-of-life situations when the decision is made to provide aggressive life-sustaining treatments that are felt to put excessive burden on patients and families.

Clinicians who see patients at the end of life may be particularly vulnerable to moral distress. For those of us who serve as consultants, our involvement in a case is at the discretion of the attending physician. In cases such as Mrs. L’s, we feel constrained by our role as advisors to the consulting physicians and the expectation of professional courtesy towards other physicians’ decisions. When we serve as attending physicians ourselves, our ability to relieve patient suffering may be limited by the family’s preference that every possible life-sustaining measure be taken.

Moral distress is also a common problem in the nursing field, particularly critical care nursing. For clinicians in any of these roles, moral distress arises when the system or other people interfere with our ability to relieve a dying patient’s suffering.

In the nursing literature, moral distress has been shown to contribute to decreased job satisfaction and to burnout. The American Academy of Critical Care Nurses recommends addressing moral distress with a four-step process:

- Ask: You may not even be aware that you are suffering from moral distress. Signs of moral distress may include physical illnesses, poor sleep, and fatigue; addictive behaviors; disconnection with family or community; and either over-involvement or disengagement from patients and families.

- Affirm: Validate the distress by discussing these feelings and perceptions with others. Make a commitment to caring for yourself by addressing moral distress.

- Assess: Identify sources of your distress, and rate its severity. Determine your readiness to act, and what impact your action would have on professional relationships, patients, and families.

- Act: Identify appropriate sources of support, reduce the risks of taking action when possible, and maximize your strengths. Then you may decide to act to address a specific source of distress in your work environment.

In Mrs. L’s case, the consultant discussed the case with the interdisciplinary team, receiving support for her concerns. Despite fear of negative repercussions from the primary service, she called the patient’s son herself and gently explained the signs of suffering that Mrs. L was showing. He agreed that his mother should have low-dose morphine. The primary team added this order without any expressed objections to the consultant stepping over her boundaries. Mrs. L died a few days later.

References

1. Weissman, D. Moral distress in palliative care. Journal of Palliative Medicine. October 2009, 12(10): 865-866.

2. The American Association of Critical Care Nurses. The 4 A’s for managing moral distress. (free pdf)

Thursday, June 17, 2010 by Christian Sinclair ·

Tuesday, November 24, 2009

In consideration of the many family dinners that will occur over the next few days of the Thanksgiving holiday, we are hosting (along with several other medical bloggers) a guest post from Engage with Grace and the One Slide Project. This post will stay at the top of this blog from Tuesday the 24th until Sunday the 29th. You can also join the Engage with Grace group on Facebook.

Have a safe and meaningful Thanksgiving!

Some conversations are easier than others

Last Thanksgiving weekend, many of us bloggers participated in the first documented “blog rally” to promote Engage With Grace – a movement aimed at having all of us understand and communicate our end-of-life wishes.

It was a great success, with over 100 bloggers in the healthcare space and beyond participating and spreading the word. Plus, it was timed to coincide with a weekend when most of us are with the very people with whom we should be having these tough conversations – our closest friends and family.

Our original mission – to get more and more people talking about their end of life wishes – hasn’t changed. But it’s been quite a year – so we thought this holiday, we’d try something different.

A bit of levity.

At the heart of Engage With Grace are five questions designed to get the conversation started. We’ve included them at the end of this post. They’re not easy questions, but they are important.

To help ease us into these tough questions, and in the spirit of the season, we thought we’d start with five parallel questions that ARE pretty easy to answer:

Silly? Maybe. But it underscores how having a template like this – just five questions in plain, simple language – can deflate some of the complexity, formality and even misnomers that have sometimes surrounded the end-of-life discussion.

So with that, we’ve included the five questions from Engage With Grace below. Think about them, document them, share them.

Over the past year there’s been a lot of discussion around end of life. And we’ve been fortunate to hear a lot of the more uplifting stories, as folks have used these five questions to initiate the conversation.

One man shared how surprised he was to learn that his wife’s preferences were not what he expected. Befitting this holiday, The One Slide now stands sentry on their fridge.

Wishing you and yours a holiday that’s fulfilling in all the right ways.

(To learn more please go to www.engagewithgrace.org. This post was written by Alexandra Drane and the Engage With Grace team. )

Tuesday, November 24, 2009 by Christian Sinclair ·

Thursday, May 7, 2009

By Ellen M. Redinbaugh, PhD

Originally posted at the Institute to Enhance Palliative Care, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

CASE:Mr. J was a 39 year-old white married male who came to the hospital for a tissue biopsy and was subsequently diagnosed with advanced adenocarcinoma of unknown primary origin. His disease had progressed to the point where the tumors could not be debulked. The previous week Mr. J had been working full time and leading a very active lifestyle, so his diagnosis and prognosis came as a shock to him and his family. The primary medical team consulted the Palliative Care Team (PCT) to assist with symptom management, discussion of treatment options and goals, and planning of end-of-life (EOL) care.

Once Mr. J became physically comfortable and accepting of his poor prognosis, he voiced concerns about how to talk to his 6 year-old son and 8 year-old daughter about his illness and likely death. The RN for the PCT provided Mr. J with books that aid parents in discussing death and dying with children, and the behavioral medicine specialist with the PCT assisted Mr. J in applying these materials to the conversation he would have with his children.

First, as a means of understanding each child’s developmental level, the behavioral medicine specialist asked Mr. J to simply talk about his two children – how they spent their time, what subjects were they good at in school, and what, if any, exposure they had to the death of a loved one or pet. This discussion naturally led into Mr. J identifying words and concepts about illness and death that his children would understand. Mr. J decided he would say the following to his children, “Sometimes people get sick and the doctors can cure them. Sometimes people get sick and the doctors can’t cure them. The doctors don’t think they can cure me, but I am hoping for a miracle because I don’t ever want to leave you.”

Although his message was brief, Mr. J feared he would emotionally break down when having this conversation with his children. He wanted to be “strong” for them so that they would not be too frightened. To promote his sense of self-control Mr. J practiced his conversation with the behavioral medicine specialist who in turn coached him on breathing techniques that would help him stay in control of his emotions.

The practice helped, but Mr. J still feared that “we’ll all end up crying and that’s not going to any of us any good in the long run.” So then the behavioral medicine specialist worked with him on identifying specific ways in which he was a father to his children, e.g., he helped his children with their homework and he read to them every night before they went to bed. She suggested that after he gives them the bad news and answers their questions, Mr. J might reassure his children that he’s still going to help them with their homework and read to them every night.

DISCUSSION:

Young children who are informed of their parents’ terminal illness are less anxious than those who are not told , but many terminally ill parents are daunted by this emotionally stressful task. Deciding how to break the news to children is made more difficult when taking into account the developmental level of each child. Palliative Care Teams often have several books available that guide parents through the process of discussing death and dying with their children. Parents’ abilities to apply the information in these books can be further enhanced with a session provided by the behavioral medicine consultant. The individual session allows parents to tailor their approach to their own families and to practice having and controlling very powerful feelings.

References

1. Rosenheim, E., Reicher, R. (1985). Informing children about a parent’s terminal illness. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Disc. 26:995-998.

2. Siegel, K., Raveis, V., Karus, D. (1996). Pattern of communication with children when a parent has cancer. In L. Baider & L. Cooper (Eds) Cancer and the family, pp 109-128. John Wiley and Sons: New York.

Thursday, May 7, 2009 by Christian Sinclair ·

Monday, April 20, 2009

By Rev. Dale Anderson, B.A., M Div.

Originally posted at the Institute to Enhance Palliative Care, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

Case: During a weekly Palliative Care Consult meeting, it was discussed that if D, 53-year-old woman with congestive heart failure, did not receive a heart transplant within several weeks to a few months at the most, she would probably die. I felt led to visit her, even though she was not on my normal unit rounds. On the initial visit, D was welcoming when I stopped by her room. After introducing myself as a Protestant staff chaplain, I inquired about her pain. D told me how uncomfortable she was and how she felt so limited by her physical condition. When I asked how she was coping with any other areas of suffering in her life, her lips quivered and her eyes filled with tears as she told of the burdens in her soul…deep, personal stresses in her life that continued to that very day. She had tearfully vented for about an hour, as I reflectively listened and reassured her that every word was confidential and I was there for her to listen, if nothing else.

After hearing her life’s trials, it was important to let her know, as a chaplain and pastor representing Christ’s church, that God could help not only with the treatment of the pain in her heart but also with the trauma of her suffering soul. I prayed for her and the medical team that would work with her and those behind the scenes to care for her, to harvest the new heart and skillfully transplant it into her body; as well as for the opportunity to deal with some of the issues of suffering that were plaguing her. Thankfully, the issues that she was suffering from began to be addressed within her family as the real possibility of D’s death triggered the process of reconciliation. As those issues began to be resolved and forgiveness and harmony blessed her life, hope and new meaning for her life made the anticipated pain of transplant more tolerable. D was sent home with a VAD long enough to appreciate how some of the stress that existed in the home before had dissipated. Within 48 hours D was back in for her heart transplant.

Surgery went very well, and D was out of the ICU with few complications. Yet, once D was on a step-down unit and dealing with post-operative pain in her body and the anxiety and depression that ensues after transplantation, she was troubled by her years of living as a sufferer. It was reassuring when she made her suffering known.

Thankfully, the issues were addressed by those that contributed to her suffering within her family, and positive changes brought meaning back into her life. D did embrace her new life with meaning and purpose, and as she healed from the pain of the transplant, it was made bearable by the liberation from suffering.

This was a process that was not resolved as in our modern media. It was assisted in by others in the Palliative Care Team, the Transplant Team, Unit Staff, Pastoral Care, Providence, and, of vital importance, D’s family members who realized D’s mortality and took ownership of her suffering and their contribution to the dysfunction in their household.

In many of the rooms of the hospital are laminated Comparative Pain Scales with 1 being expressed as :) demonstrating No Pain to 10 being Unbearable/Excruciating Pain. Modern technology addresses this pain well. Suffering of the soul, mind, psyche, what ever terminology you are comfortable with, also needs to be addressed with awareness and compassion. Everyone should participate. According to Thomas R. Egnew, “Suffering arises from perceptions of a threat to the integrity of personhood, relates to the meaning patients ascribe to their illness experience, and is conveyed as an intensely personal narrative.”

While the medical community has established procedures, protocols, and treatment plans that factor in typical emotional responses, suffering is personal, individual and commonly expressed as a narrative that needs the freedom and respect to be presented and the dignity to be acted on to reestablish meaning and significance. Pastoral Care is one piece of the solution, but by far, not the only piece in total patient care.

References:

1. Mayo Clinic on Chronic Pain; Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Kensington Publishing Corp., NY, NY. 1999

2. Egne, TR. Annals of Family Medicine; Suffering, Meaning and Healing: Challenges of Contemporary Medicine. LICSW. Volume 7 No 2. March/April 2009

Monday, April 20, 2009 by Christian Sinclair ·

Thursday, March 12, 2009

By Tamara Sacks, MD

Originally posted at the Institute to Enhance Palliative Care, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

Case

CH is a 56-year-old woman with metastatic breast cancer to bone, liver and brain. She is admitted to the hospital with increasing lethargy and a marked decrease in her oral intake. She has also not had a bowel movement for 10 days. Further interview reveals that she has been on a fentanyl patch 75 mcg for months, senna and colace, and hydrochlorothiazide. Her diuretic is stopped and she is placed on intravenous fluids. Except for dehydration, a metabolic work up is unremarkable. Her exam reveals hypoactive bowel sounds, a scaphoid abdomen with palpable mobile masses, and soft stool in the rectal vault. She is disimpacted. No active bowel movement follows despite suppositories. She is also not able to retain enemas. She has increasing nausea and anorexia. Given her inadequate response to a bowel regimen from below and inability to tolerate an oral regimen, she is dosed with methylnaltrexone subcutaneously x1. She has a large formed bowel movement 2 hours later.

Discussion

Constipation is a well recognized side effect from opioids. Tolerance does not occur. In fact, the dose that can cause constipation is ¼ of an analgesic dose. Opioids exert their constipating effects by decreasing GI motility, gastric emptying, increasing ileocecal valve tone, increasing fluid resorbtion, and decreasing the reflex to defecate.

Methylnaltrexone (MNTX) is a mu receptor antagonist that unlike naloxone does not cross the blood brain barrier as it is a quaternary amine. Naloxone has been used in the past for opioid induced constipation. However, this use has also been associated with opioid withdrawal and decreased pain relief. MNTX was approved for the treatment of opioid induced constipation by the FDA last year. Given its expense, many institutions have tried to limit its use. Our institution has made a Palliative Care consult one of three consultation services that can approve dosing.

The phase three clinical trials that led to approval of MNTX involved patients either enrolled in hospice or as part of a palliative care program, and opioids were thought to be the primary cause of the constipation. They must have been receiving opioids for two weeks and on a stable opioid and laxative regimen for three days.

Enrolled patients had had no bowel movement in greater than 48 hours or had had less than 3 bowel movements the week prior. Bowel obstruction, fecal impaction or other acute abdominal processes were ruled out. In addition, patients with peritoneal dialysis catheters and fecal ostomy bags were excluded. While 80 percent of the patient population had cancer, patients with cardiovascular disease, AIDS, dementia, and COPD were also included. MNTX is administered subcutaneously based on the patient’s weight. After administration of MNTX, greater than or equal to 50% of the study group had a bowel movement within 4 hours. Most patients had a bowel movement within 30-70 minutes. As compared to placebo, the most frequent side effects were abdominal cramping, nausea, dizziness, increased body temperature and flatulence. However, the number of patients who discontinued therapy secondary to side effects was similar to that in the placebo group. No decrease in pain control or signs of opioid withdrawal were noted as compared to the placebo group.

There are many medications and dosage forms that are available for opioid induced constipation. Previously, routes of administration have been oral and rectal. Dysphagia, nausea or decreased mental status can greatly hinder an adequate regimen by mouth. Rectal routes of suppositories and enemas can also be tried. Inability of the patient to participate can limit effectiveness of enemas. In properly selected patients, MNTX may be able to aid in relief of opioid constipation without adversely affecting pain control

References:

1. Thomas, Jay et. al. Methylnaltrexone for Opioid Induced Constipation in Advanced Illness. 2008. NEJM 358 (22): 2332-2343.

2. Yuan, Chun-Su. Methylnaltrexone Mechanisms of Action and Effects on Opioid Bowel Dysfuction and Other Opioid Adverse Side Effects. The Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 2007. 41: 984- 993

Thursday, March 12, 2009 by Christian Sinclair ·

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=e6c24c53-1899-459f-8a6f-9e762a62562f)